Bainbridge Island Japanese American Memorial Ignores Wartime Realities

(page 3 of 5)

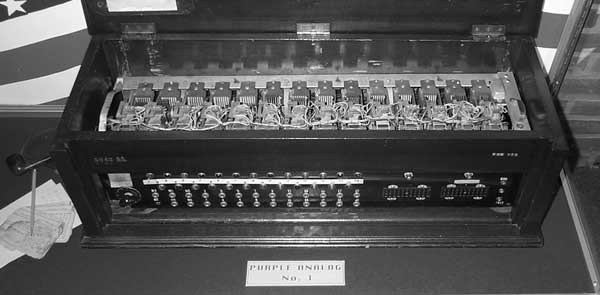

Breaking the Code

In September, 1940 the Army Signal Intelligence Service broke the Japanese diplomatic code. Through hard work, inspiration, and luck, the same team was able to build a machine that exactly duplicated the operation of the Japanese cryptographic machine, and from then until after the war the U.S. was able to read most of Japan's significant, secret messages to and from its overseas offices and agents.

From late January, 1941 on, it became indisputably evident that Imperial Japan was directing the operation of espionage in the U.S., and that both Japanese Americans and Japanese citizens were involved. This information came from an unimpeachable source: the Imperial Japanese government itself. It came as a result of our breaking their top diplomatic code and decrypting messages intercepted by highly significant U.S. listening posts such as Station "S" on Bainbridge Island.

The information thus gathered was given the cover-name "Magic" because it seemed that only magicians could have produced it.

The information was so sensitive and important that its release was limited to a handful of top civilian and military leaders. For example, Lt. Gen. John L. Dewitt, the man most often blamed for the "racially motivated" evacuation, J. Edgar Hoover, FBI Chief, and various others who opposed the evacuation at the time were not aware of Magic intelligence. Not one person who was privy to the Magic intercepts ever opposed the evacuation.

On January 30, 1941, Imperial Japan notified its embassy in Washington, D.C. that the Japanese Government was switching its emphasis from propaganda to intelligence gathering; that efforts should be organized to operate in the event of war and include,

"Utilization of our 'Second Generations' [U.S. citizens] and our resident nationals. (In view of the fact that if there is any slip in this phase, our people in the U.S. will be subjected to considerable persecution, and the utmost caution must be exercised.)" [Note 15]

In May, 1941, two reports were intercepted which outlined progress in establishing intelligence networks. One was from Los Angeles and the other from Seattle. (All other such reports were probably sent by more secure means such as couriers. Shortly after these two were intercepted, consulates were warned to send sensitive information by courier.)

Los Angeles reported,

"We have already established contacts with absolutely reliable Japanese in the San Pedro and San Diego area, who will keep a close watch on all shipments of airplanes and other war materials, and report the amounts and destinations of such shipments. The same steps have been taken with regard to traffic across the U.S. Mexican border.... We shall maintain connection with our second generations who are at present in the (U.S.) Army, to keep us informed of various developments in the Army. We also have connections with our second generations working in airplane plants for intelligence purposes." [full text]

Seattle reported,

"We are securing intelligences (sic) concerning the concentration of warships within the Bremerton Naval Yard, information with regard to mercantile shipping and airplane manufacturer, movements of military forces, as well as that which concerns troop maneuvers.... With this as a basis, men are sent out into the field who will contact Lt. Comdr. OKADA and such intelligences (sic) will be wired to you in accordance with past practice....Recently we have on two occasions made investigations on the spot of various military establishments and concentration points in various areas. For the future we have made arrangements to collect intelligences (sic) from second generation Japanese draftees on matters dealing with the troops...." [full text]

While no other planning reports were intercepted, numerous operational reports were. A June 23, 1941 Seattle message reported on:

"Ships at anchor on the 22nd/23rd (?):"

And then stated:

"(Observations having been made from a distance, ship types could not be determined in most cases.)" [full text]

One long-time Bainbridge resident who served in the navy at the time recalls when the British warship Warspite quietly sailed into Bremerton at night and was docked for repairs among a number of U.S. ships. On August 16, 1941 a message from Seattle to Tokyo said,

"According to a spy report, the English warship Warspite entered Bremerton two or three days ago." [full text]

A September 20, 1941 message gave detailed information on warships in Bremerton, and the repairs being made. [full text]

The current popular account of the Japanese evacuation blames racism, hysteria, and lack of political will as the causes. It ignores, denies, excuses and justifies the outrageous conduct of large numbers of ethnic Japanese in the U.S. at the time.

If blame is to be assigned for the evacuation, Imperial Japan deserves top billing. It used ethnic Japanese for its war planning purposes, thus casting warranted suspicion on them as a group. Next are those Japanese Americans and Japanese citizens who participated in suspicious and later treasonous activities.

Whatever else is said about the evacuation, there is no doubt it prevented the type of subversive activity that so successfully supported Imperial JapanÕs war efforts and invasions elsewhere. It also eliminated the need for costly and time consuming prosecutions.

| Back: The Japanese |

Reference Notes

Note 15

This message was key in the establishment of an intelligence operation in the U.S.